What is the future of Prime Central London?

Prime Central London has had to adapt and evolve to meet the changing needs of the rich and famous for hundreds of years. It now faces new challenges – not just thanks to Brexit and the immediate impacts of the global pandemic – but also longer-term issues like changing lifestyle preferences and climate change.

Future Residential Series

Breaking the cycle

The discretionary nature of many property purchases in Prime Central London means it responds quickly to changes in sentiment and is often the first market out of any downturn. The housing market was already firmly into its second half prior to the pandemic. House prices were rising fastest in the north of England and stagnant or falling in London. Despite predictions of a downturn, the pandemic appears to have continued the current market cycle. It has also added further complications with demand shifting away from urban areas. With both these factors and constrained international travel, Prime Central London is one of the few housing markets that has not seen booming prices over the last six months.

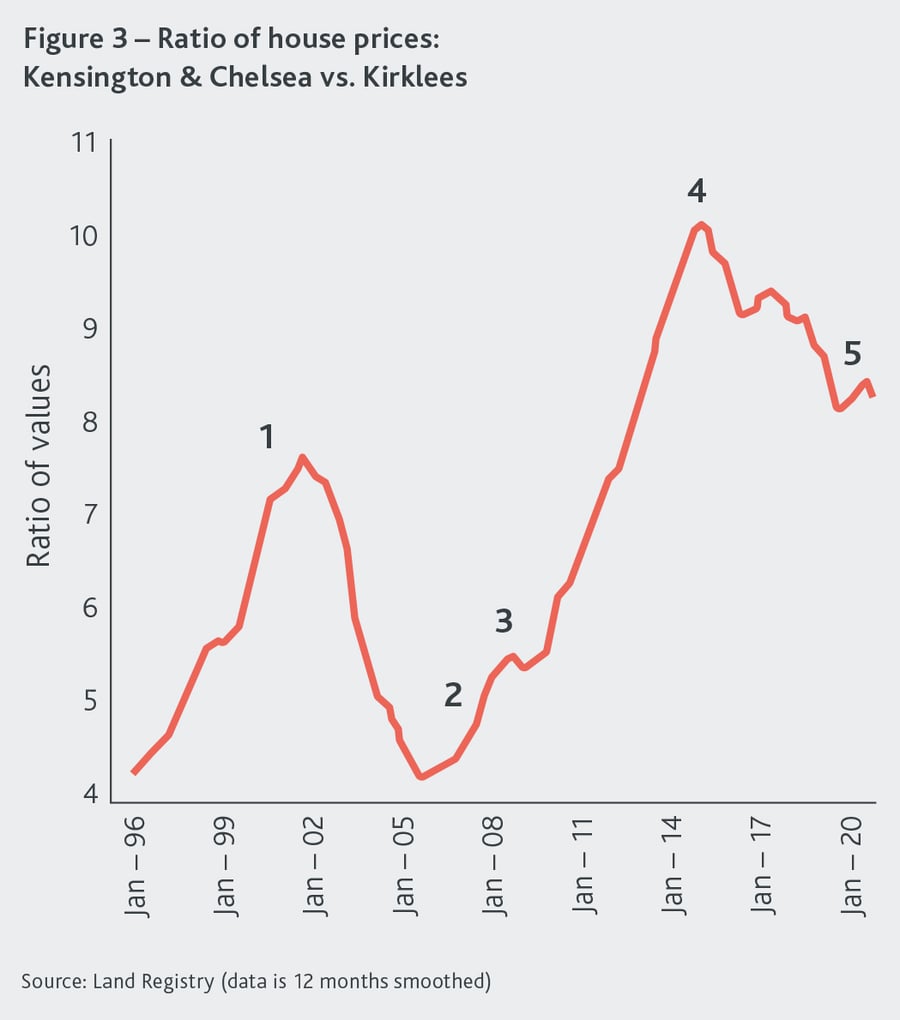

The market cycle trend has not been kind to Prime Central London in recent years. This is highlighted by Figure 3 which shows the ratio of house prices in Kensington & Chelsea to those in Kirklees in Yorkshire. The chart illustrates the relationship between Prime Central London and the North of England over the past 25 years with a rising line representing a growing price premium for Prime Central London and a falling line representing a falling price premium. The chart shows that Prime Central London has been under-performing since 2015 but, compared to even the 2000 peak, the current ratio to a typical northern market is still relatively high. This raises the question of whether the pandemic will further reinforce the existing market cycle or can Prime Central London bounce back when people return to cities in greater number and the global elite start travelling again.

The ‘dotcom’ boom of 2000 fed the first peak (1), with the trend then reversing as values grew strongly in the Midlands and North of England, along with them starting to fall in central London.

The ratio bottomed out in 2005. The final stage of this cycle was for higher value markets in London and the South East to see a further burst of inflation in 2006-07 (2).

The global financial crisis in 2008 caused house price falls of around 20% across most UK markets (3). Central London fared slightly worse but started to bounce back much more quickly than other areas, and the ratio gradually climbed to a new peak of over 10:1 in early 2015 (4).

Since this point Prime Central London values have been relatively weakened (5) by a series of policy changes and geopolitical events, underperforming other markets.

Risks on the horizon

In the immediate future, international travel will recover – from a very low trough – and more workers will return to their offices for at least some part of the week. This points to some level of recovery in demand from both discretionary buyers and those more driven by a ‘need’ to be in Central London. We also know that levels of wealth for the potential Prime Central London buyer/investor demographic have grown significantly through the pandemic, so the ability to buy remains strong.

On the supply side, the continuing low inflation and low interest rate environment reduces the cost of holding valuable properties. But the Government appears to be open to significant spending to enhance the post-Covid recovery, potentially creating more inflationary conditions and increasing the appeal of alternative investments. Higher inflation could drive demand for real assets, but with the oft-mooted introduction of wealth taxes – which may be an easier political sell if framed as ‘paying for the pandemic’ – the drivers in favour of selling may grow.

The risk of a wholesale exodus from large cities is very slim, either in terms of living or working, despite some of the more sensationalist headlines in the past 15 months. But that does not mean that there will not be any changes or that these won’t have an impact on Central London real estate.

Drivers of change

Changing lifestyle preferences might mean moving out of London to a completely rural location for some people, but equally it may just mean trying to find a flat with outdoor space or nearer to a park. We are unlikely to see the full impact of any shift until the pandemic is long behind us. Cluttons’ agents have already noted lower demand for flats without gardens or balconies. The requirement for flats to be compliant with fire safety legislation, via an EWS1 form, has also dampened demand in this part of the market.

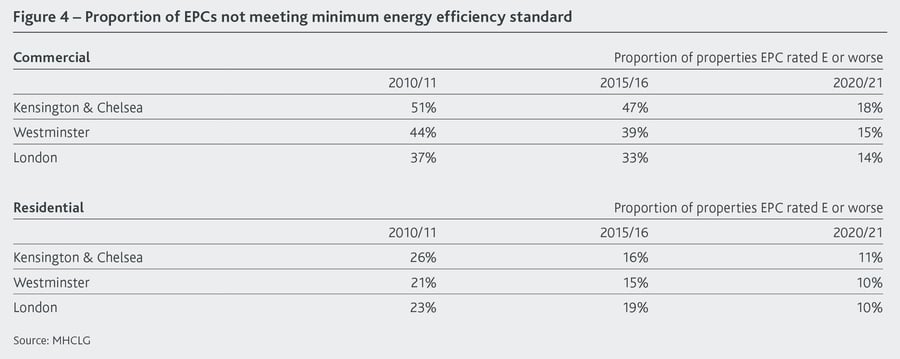

A longer-term issue is how suitable the existing building stock will be for its intended use over the rest of the century. Minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES) for letting property were introduced in 2018 (with the rules being tightened in 2020 for residential / 2023 for commercial). They already appear to have had an impact on buildings in Central London. EPC ratings across both sectors have improved over the past five years and, despite a high proportion of local period buildings, the percentage of potentially non-compliant buildings in the commercial sector has fallen to sit in line with the London average, as shown in Figure 4.

In the residential sector ratings overall are better but there has still been significant improvement over the past decade. The central boroughs have been more in line with the London average over this period, but the costs of bringing homes up to standard can be significant and may lead to inefficient homes losing value. This trend could accelerate if the emerging market for green mortgages and finance (i.e. cheaper rates for more efficient buildings) becomes more widespread.

Five key trends

The post-pandemic recovery is certain to bring change to the Prime Central London market – creating new trends, accelerating some existing ones, and perhaps hampering others.

- New development has been driving an eastward and southward expansion from the traditional core of Prime Central London, but this could be slowed if working patterns don’t return to the common pre-pandemic baseline. ONS surveys suggest over 90% of higher income employees expect a mix of homeworking and returning to their usual workplace. Without being based in the office five days per week, some employees may choose to live further from the city’s employment centres.

- Many Prime Central London submarkets are home to established communities of various nationalities. The pandemic has probably seen London’s population fall, with some estimates suggesting over half a million non-UK born residents have left the capital. The GLA’s detailed analysis also highlights recent falls. The impact on the housing market will depend on whether any falls are temporary reactions to the pandemic or longer-term structural changes. For example, Brexit will limit free movement to and from EU nations and could make it difficult for some previous residents to return. This could trigger a shift in supply and demand in some locations.

- ‘Lockdown-proofing’ is now a key consideration for many potential homebuyers. Access to nearby parks and green space, somewhere to set up a home office, and balconies or gardens, have all moved up the priority list, along with digital connectivity and energy efficiency. A recent survey by Nationwide found potential movers favouring less urban areas across all age bands. Within London, areas with higher proportions of suitable stock and more of a ‘village feel’ may become more sought after.

- High rise flats have also seen a separate fall in demand due to building safety concerns following the tragedy at Grenfell. This has led to uncertainty in valuations for homes in tall buildings, in some cases limiting the market to cash buyers. Areas with more houses and lower-rise mansion blocks could see more demand until these issues are resolved.

- The pandemic may leave Prime Central London with an excess of office and retail properties: Cluttons Q4 Office Market Review reported that take-up in Central London was 64% lower than the five-year average and availability was 24% higher. If demand for lower quality commercial stock remains low, property owners have the option of upgrading, or taking advantage of permitted development rights to convert to residential, potentially increasing the number of residential properties in some submarkets.

The evolution of Prime Central London articles

To read the complete The evolution of Prime Central London report, follow the links below or use the Download report button.

- The evolution of Prime Central London Report

- What is Prime Central London?

- Prime Central London’s global demand & local markets

- What is the future of Prime Central London?